Gallery › Rogues Gallery

America in the 1920s and 1930s: The Rising Tide of Anti-Semitism

For most of its collective history, American Jewry has enjoyed the full benefits of all that this nation has offered to those immigrant groups seeking a freer and better life. Unlike their European experience, Jews in America did not have to face the wrath of an established anti-Jewish religion or the whims of a government or national leader who decided they were no longer a part of the “nation.”

But that was not always the case. Anti-Semitism in America reached dangerous levels in the years between World War I and World War II and was practiced in different ways by highly respected individuals and institutions. By 1939, one researcher estimated that at least 800 organizations in the United States were carrying on “a definite anti-Semitic propaganda.” Private universities, summer camps, resorts, and places of employment all imposed restrictions and quotas against Jews, often in a public way. Jews were accused of a lack of patriotism and character by American titans of industry and leading religious voices. Jews faced the threat of physical attacks and often were the victims of vicious beatings. It was a time of terror for the American Jewish community.

The following “rogues gallery” allows the reader to encounter just some of those who were responsible for this time of terror. They are not relics of an ancient and bygone era. Their ideas and their calls for action against what they perceived as the destructive influence of American and world Jewry contributed to the murder of six million Jews during the terrible years of the Holocaust. And while they are gone, their beliefs are not. They live in the hundreds of internet sites devoted to hatred of Jews and Judaism; they live in the pages of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion readily available in bookstores around the world; and they live in the efforts to de-legitimize the State of Israel and in the calls for its destruction. They live as a warning to us all.

Teacher and Docent Curriculum Guide/Discussion Sheet

Audio version of introduction read by Aleshea Harris (2:18)

Jean M. Peck is a writer, editor, and educator who lives in Portland, Maine. She is the author of two books: At the Fire's Center (University of Illinois Press) and, with Abraham Peck, Maine's Jewish Heritage (Arcadia Press). She is an adjunct professor of English at the University of Maine, Augusta.

Father Charles E. Coughlin: The High Priest of Hate Radio

During the 1930s and early 1940s, as many as 30 million Americans gathered around their radio sets on Sunday afternoons to listen to the “Golden Hour of the Little Flower” program.

The voice they heard belonged to Father Charles E. Coughlin, 1891-1979, the Catholic priest who headed the local parish in Royal Oak, Michigan known as the Shrine of the Little Flower Church. At its height, this radio program was heard by more Americans than “Howard Stern, Rush Limbaugh, Paul Harvey and Larry King combined.”

Coughlin was a Canadian-born demagogue who mixed a message of social justice for the poor with a viciously anti-Communist, anti-Semitic rhetoric that frightened an American Jewish community that was already experiencing the worst anti-Jewish prejudice in its history. He charged that the masterminds of the Communist movement were primarily Russian Jews. He accused American Jewish financiers such as Jacob Schiff and Felix Warburg with providing the money to support the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

But Coughlin was not only a master of the airwaves. He also reached the American public through the pages of his magazine, Social Justice, which not only repeated his anti-Jewish sentiments, but published the anti-Semitic piece of propaganda, “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” that accused Jews of plotting to seize control of the world. A decade earlier, the American industrialist Henry Ford had published the same lies in his newspaper, the Dearborn Independent.

Coughlin also organized a popular mass movement called the “Christian Front.” For a number of years, into the early 1940s, members of the Christian Front carried out physical assaults on Jews in cities such as Boston and New York.

Coughlin’s anti-Semitic activities were not unknown to authorities in Nazi Germany. After a New York radio station decided to drop his program because of numerous complaints from Jewish groups, a German newspaper wrote that “Jewish organizations camouflaged as American… have conducted such a campaign… that the radio station company has proceeded to muzzle the well-loved Father Coughlin.” A New York Times correspondent in Germany reported that Coughlin had become “the hero of Nazi Germany.”

Finally, after America entered the Second World War in December 1941, both the United States government, which banned Social Justice, and the American Catholic Church, which threatened to strip Coughlin of his priestly authority, put a stop to his activities.

Audio version of introduction read by Aleshea Harris (2:59)

Audio interview with Dr. Abraham Peck (9:13)

Father Charles E. Coughlin frightened the American Jewish community of the 1930s with his vicious yet influential radio tirades against Jews and Judaism. What dangers did Coughlin pose as he mesmerized millions of American listeners with his message of anti-Semitism, anti-capitalism and pro-fascism? Do today’s “shock” radio and television commentators have the potential to become contemporary Father Coughlins, and is the internet an accessory or an antidote to such possible threats?

Henry Ford: The International Anti-Semite

Henry Ford, 1863-1947, was a gifted American inventor and businessman who gained nearly as much fame for his anti-Semitic views as for his pioneering role in the development of the American car industry.

Ford was a man of enormous contradiction: on the one hand he yearned for a return to the rural life into which he was born in a fundamentalist Christian area of southeastern Michigan. On the other hand, he contributed enormously to the growth of an industrial society that robbed agrarian America of its economic future and lured its farm men and women to the factories of the big city.

Ford did not even know any Jews until his early twenties. What he did know and share were the anti-Jewish images portrayed in the enormously popular nineteenth-century Readers compiled by William Holmes McGuffey that introduced an entire generation of young Americans to stereotypical images of the “alien” Shylock (“an inhuman wretch, incapable of pity”) the opponents of the apostle Paul (“the Jews caught me in the temple and went about to kill me”), images that painted Jews as “strangers to the morality contained in the Gospel.”

He blamed the “Jewish moneylenders” and the “Wall Street kikes” for gaining control of the world’s economy and destroying the moral backbone of “his” America. Yet he maintained a strong friendship with a neighbor, the well-known Detroit rabbi Leo Franklin, presenting the rabbi with a new car at the beginning of each year. Yet, when Ford’s anti-Semitism became a national issue, and Franklin sent back his latest gift, he had absolutely no idea why Franklin refused to take the car. “What’s wrong, Dr. Franklin,” he wrote to the rabbi. “Has something come between us?”

The reason for Franklin’s action was series of articles, beginning in 1920, published in Ford’s newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, that for 91 successive weeks produced excerpts of the notorious anti-Semitic forgery, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, written at the beginning of the twentieth century by Czarist Russia’s secret police. The Protocols substantiated everything that Ford had come to believe about the Jewish world conspiracy. Soon after the Independent began to publish the Protocols, they were published in book form as the International Jew (four volumes between 1920 and 1922). The volumes were translated into numerous languages and read by an obscure Austrian war veteran named Adolf Hitler who praised Ford for his insights in the second volume of his magnum opus Mein Kampf (My Battle).

For much of the 1920s, the Dearborn Independent kept up its attack on the Jewish community and did untold damage to the place of Jews in American society. It was only in 1927, when a libel suit brought by a Jewish businessman threatened to force Henry Ford to appear as a witness in front of a judge and jury and the slumping sales of his mass-produced cars, that Henry Ford finally offered a public apology for the activities of his newspaper.

In a public statement drafted entirely by the prominent American Jewish lawyer and communal leader Louis Marshall and signed sight unseen, Henry Ford promised “that the pamphlets which have been distributed throughout the country and in foreign lands will be withdrawn from circulation [and] that in every way possible I will make it known that they have my unqualified disapproval.”

Ford took no personal responsibility for any of the anti-Semitic propaganda published in the Dearborn Independent, blaming instead two trusted aides who he claimed created the anti-Jewish diatribes without his knowledge.

In the end, the man of contradictions who helped create an international atmosphere of Jew hatred both at home and abroad, whose The International Jew was translated into sixteen languages and distributed in the millions, never acted on the promises of his public apology. He remained a constant source of support for such American anti-Semites as Father Charles Coughlin and the Reverend Gerald L.K. Smith and received his most cherished accolade in the form of a medal presented to him in 1938 by the Nazi German government, “the highest honor given by Germany to distinguished foreigners.”

What was the contradiction? In the spring of 1945, the founder of the Ford Motor company sat with one of his executives viewing recently filmed newsreels of the piles of corpses and human skeletons discovered in Nazi concentration camps. At that moment he suffered one of several massive strokes that would rob him of his mental and physical capacities and from which he would never recover until his death in 1947.

Audio version of introduction read by Aleshea Harris (5:08)

Audio interview with Dr. Abraham Peck (5:55)

What drove a major captain of American industry, Henry Ford, to publish false but damaging conspiracy theories about American and world Jewries? Ford grew up in the rural Midwest where Jews were relatively unknown. What would motivate him to embark on such an anti-Semitic road and become for the American Jewish community of the 1920s “Public anti-Semite Number One?” Would and could his Ford Motor Company make amends for the noxious actions of its founder?

Philip Johnson: Form and Fascism

Philip Johnson, 1906-2005, is generally regarded as one of the country’s greatest architects, a man whose 1932 show on the International Style at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) introduced the American public to modern architecture and whose designs symbolized the development of a uniquely American form of that modernism. Yet, Johnson is also celebrated for abandoning classical modernism two decades later in order to experiment with a number of different styles that held more closely to the changing tastes of the time.

His is a biography of the highest rank, a “towering figure” who reigned supreme in the history of twentieth century American culture. He was awarded an American Institute of Architects Gold Medal and the first Pritzker Architecture Prize, one of the most prestigious awards in the architectural community. Yet his extraordinary resume did not tell the full story of Philip Johnson’s life and career.

For nearly a decade, in the 1930s and into the 1940s, Philip Johnson did not focus on architectural form or design. Instead, he worked on the form and design of an American fascist society based upon the model of Nazi Germany. In 1932, the same year as his historic MOMA show, he visited Germany and observed Adolf Hitler at a Nazi rally near the city of Potsdam. Philip Johnson fell in love with National Socialism.

Two years later, he resigned his position with MOMA and set out with a colleague, Allan Blackburn, to strengthen an America already infected with the disease of anti-Semitism. Johnson and Blackburn sought to create their own version of the Nazi Party, which they called the “Nationalist Party” and the “Gray Shirts,” modeled on the Nazi Storm Trooper Brown Shirts. When the party failed to attract enough members, both men travelled to Louisiana to offer their services to Huey Long, the controversial populist governor of Louisiana. Distrustful of two Harvard graduates from New York, Long refused their support.

Johnson and Blackburn found their spiritual home in Michigan, and joined Father Charles Coughlin in his campaigns against the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the negative influence of Jews in American life. Johnson and Blackburn supervised the printing of Social Justice, Coughlin’s anti-Semitic magazine, and organized a massive rally for Coughlin in Chicago, where more than eighty thousand spectators heard the “radio priest’s” anti-Communist and anti-Semitic rantings. Coughlin stood on a podium designed by Johnson that was modeled on the one used by Adolf Hitler at the 1932 Potsdam rally.

In 1938, Johnson was invited by the German government to attend a summer program in Berlin to learn the basics of Nazism and to hear Hitler speak at the greatest of the Nuremburg rallies, immortalized in the film” Triumph of the Will,” by the director Leni Riefenstahl.

In his capacity as a German correspondent for Social Justice, Johnson toured Poland just a month before the outbreak of war in September 1939. He wrote about his experience that

When I first drove into Poland… I thought I must be in the region of some awful plague…. In the towns there were no shops, no automobiles, no pavements, and again no trees. There were not even any Poles to be seen in the street, only Jews!

At first, I didn’t seem to know who they were except they looked so totally disconcerting, so totally foreign. They were a different breed of humanity, flitting about like locusts. Soon I realized they were Jews, with their long black coats, everyone in black, and their yarmulkes.

A month later, at the invitation of the German Propaganda ministry, Johnson was invited to accompany German troops as they invaded Poland. He wrote to an American friend who had accompanied him to Poland a month earlier about the experience:

I was lucky enough to get to be invited as a correspondent so that I could go to the front… and so it was that I came again to the country we had motored through, the towns north of Warsaw…. The German green uniforms made the place look gay and happy. There were not many Jews to be seen. We saw Warsaw burn and Modin being bombed. It was a stirring spectacle.

By early 1940 Johnson had become directly associated with the American Fascist movement. He was investigated by several government agencies and suspected of being a Nazi spy. Under great pressure, Johnson left his political and journalistic career and enrolled as a Harvard graduate student in architecture. It was the beginning of his efforts to rehabilitate and refashion his public image.

Clearly it worked and for the rest of his career he was Philip Johnson the famous and avant garde American architect. But there were moments of reflection and regret. In the early 1990s, he told an interviewer, when discussing his involvement with Father Coughlin and his time in Nazi Germany, that “I have no excuse [for] such utter, unbelievable stupidity…. I don’t know how you expiate guilt.” One of the ways in which he sought such expiation was in designing Congregation Kneses Tifereth Israel Synagogue in Port Chester, New York. Johnson took no fee for the project because he was so grateful for the support shown him by the congregants of the synagogue.

Perhaps in designing this symbol of Judaism, Philip Johnson found a moment of internal peace. But it did not clear his record or the fact that his activities contributed to American Jewry’s decade of anti-Semitic terror.

Audio version of introduction read by Aleshea Harris (6:19)

Audio interview with Dr. Abraham Peck (5:36)

Phillip Johnson was perhaps the greatest American architect of the last half of the twentieth century. But for the better part of the 1930s he was a man in love with National Socialism and in agreement with its poisonous attitude toward the Jewish people. Yet, this man who sought to create his own American Nazi party and who traveled with German troops as they invaded Poland in September 1939, lived a life of fame and professional triumph. What does that tell us about the role of the media in exposing the vile side of the rich and famous, and has that role changed at the beginning of the twenty-first century?

Joseph P. Kennedy: Businessman, Financier, Ambassador, Anti-Semite

Joseph P. Kennedy was born in Boston in 1888 to a wealthy, prosperous, and politically influential Irish Catholic family. He grew up religious, athletic, and intelligent. Like many Kennedys before and after him, he was a graduate of Harvard.

He married the daughter of another prominent Irish Catholic family. Joe and his wife Rose, whose father was a one-time mayor of Boston, were the parents of nine children, most of whom achieved fame in their lives. Two of the Kennedy children were killed in war-time air disasters. Two sons, President John Kennedy and Senator Robert Kennedy, were assassinated while in office. His other children dedicated themselves to public service like Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts, Eunice Kennedy Shriver who founded the Special Olympics, and Jean Kennedy Smith who served as U.S. ambassador to Ireland.

A brilliant businessman, Kennedy anticipated the end of Prohibition in 1933, and made millions when his importing company became the agent for several distilling giants. The fortune he made allowed him to invest in real estate all over the country, helping him to build a huge portfolio in major American cities. Subsequently, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt ran for his first term on the Democratic ticket in 1932, Kennedy donated thousands of dollars to Roosevelt’s campaign, for which he was eventually rewarded with the ambassadorship to Great Britain.

Joe Kennedy was thrilled with his ambassadorship and the opportunities it allowed him to establish himself and his family as a part of British society. With Britain about to enter the war, however, Kennedy’s popularity with the British — and Americans abroad and at home — was short-lived due to his isolationist and pro-Nazi beliefs. He enraged Roosevelt and the State Department by requesting a personal meeting with Adolf Hitler and then meeting with a high-ranking Nazi official to offer Germany $1 billion in exchange for peace. Roosevelt ultimately recalled him from Britain and took away his ambassadorship, but Kennedy continued to press on with his anti-Semitic and pro-Nazi beliefs.

Kennedy’s friends, Roman Catholic priest Father Charles Coughlin, whose political opinions he did not always accept, and the aviator and author Charles Lindbergh, shared Kennedy’s anti-Semitic views. To Lindbergh, Kennedy wrote of his concern that when the Nazis burned and destroyed Jewish homes and synagogues on Kristallnacht (The Night of Broken Glass), it looked bad for the Nazis, because the reports of the night’s terror damaged public’s support for the Nazi movement. Kennedy made no mention of the pain and suffering of the Jewish victims of Nazi terror.

Even while he was still Roosevelt’s ambassador to Great Britain, Kennedy wrote to Father Coughlin, that “the Democratic (party) policy of the United States is a Jewish production.” He also assured Father Coughlin that Roosevelt would not be re-elected in 1940.

Kennedy made the mistake of repeating his anti-Semitic and anti-war views even after Britain was attacked by the Nazis, and spoke against sending aid to Britain, even while he was America’s ambassador to that country. In 1940, he gave an interview to the Boston Globe, in which he asserted that democracy was finished in England. He also stated that democracy might also be finished in America.

Joe Kennedy did not resume an active role in business or politics after he was asked to resign his ambassadorship. He devoted his energies to assuring the successes of his sons’ political campaigns, while continuing to build his family’s fortunes. Unfortunately, he lived long enough to endure the assassinations of President John Kennedy and Senator Robert Kennedy. Joe Kennedy died in 1969.

Audio version of introduction read by Aleshea Harris (4:17)

Audio interview with Dr. Abraham Peck (7:59)

Joseph P. Kennedy grew up in Boston, which in the 1930s was one of the most anti-Semitic cities in the United States. His views about Jews were often negative. Yet, his public career, either as a successful businessman or as a diplomat, was never harmed by such an attitude. Indeed, his wealth and political connections were clearly important factors in the public’s perception of him. The influence of Father Charles Coughlin’s anti-Jewish views coupled with Kennedy’s belief in the Roman Catholic church’s “teaching of contempt” found a particular resonance in Boston, and combined to produce a time of terror for that city’s Jewish community.

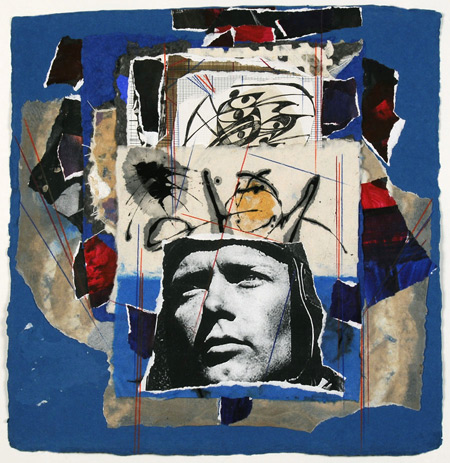

Charles Lindbergh: Fame and Shame

Charles A. Lindbergh would achieve greatness and fame as the first man to fly nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean in May 1927 in his single-seat, single-engine airplane called “The Spirit of St. Louis.” For this astonishing feat, he received America’s highest honor, the Medal of Freedom. The decades following this historic accomplishment, however, would bring him sorrow, shame, and infamy. His racist, anti-Semitic statements before, during, and after World War II, would disgrace his name and embarrass the country that once honored and revered him.

After Lindbergh’s famous flight from New York to Paris, he achieved great fame and status as an American hero. A postage stamp was issued in his honor; he was a sought-after speaker and spokesperson. Everyone wanted to meet him and to hear his opinions on the important events of the day.

In spite of his popularity, though, a great tragedy befell his family. In March of 1932, his infant son, Charles Jr., was kidnapped from his nursery in the Lindbergh’s New Jersey home. The child’s body was later discovered in the woods. A man named Bruno Hauptmann was caught, convicted, and put to death for the crime. The Lindberghs, fearing for the safety of their family, fled to Europe, where they lived until America entered World War II.

Before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Lindbergh was adamant about keeping America out of the European conflict. In an article he wrote for Reader’s Digest in 1939, he spoke of “that priceless possession, our European blood,” going on to write in his diary that Americans must “guard ourselves against attack by foreign armies and dilution by foreign races.” He testified before Congress advocating for a neutrality pact with Germany, saying that only three groups wanted America to enter the war: “the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt administration.” His trips to Nazi Germany where he met with several Nazi top officials, his writings about Germany’s “Jewish problems,” his advocacy of limiting “to a reasonable amount the Jewish influence,” and his belief that the survival of the white race was more important than that of democracy, led President Franklin Roosevelt to tell his Secretary of the Treasury that he believed Lindbergh was a Nazi. Lindbergh’s supporters denied this characterization, saying that Lindbergh was merely politically naive and inexperienced. Still, according to his great friend, Henry Ford, the automobile magnate, who hosted Lindbergh at his Detroit estate many times, “we only talk about the Jews.”

Because of Lindbergh’s anti-Jewish statements, he was denied a commission as an officer in World War II. He was able, however, to serve as a consultant to several aircraft companies for the duration of the war. His commission to the Army was restored by President Dwight Eisenhower who made him a Brigadier General in 1954. Lindbergh also served on a panel that established the United States Air Force Academy. His autobiography, The Spirit of St. Louis, won him a Pulitzer Prize.

Still, none of these accomplishments could wipe out his identity as an anti-Semite who blamed the Jews, among others, for America’s entrance into World War II. When Lindbergh died in 1974, it was amid scandal, for he had been discovered to have fathered a second family in France while still married to his wife, Anne. These facts, coupled with his anti-Semitic writings and speeches, overshadowed his reputation as a man of great achievement and accomplishment.

Audio version of introduction read by Aleshea Harris (4:17)

Audio interview with Dr. Abraham Peck (15:34)

Charles “Lucky” Lindbergh’s luck ran out when his international fame crashed around him because of his anti-Semitism and isolationist views against America’s entry into World War II. Were he and his wife, Ann Morrow Lindbergh, a member of an aristocratic American family, representative of a kind of upper class hostility toward Jews that began after the end of the American Civil War? Does such an attitude, expressed through Ivy League quotas against Jews, restricted country clubs and professional opportunities, continue today? How has the creation of the State of Israel and the ongoing conflict between Israel and the Palestinians affected such attitudes and the creation of the so-called new anti-Semitism?

View the Classroom Learning Sheet and Activities | Back to top of page