Gallery › Warsaw Ghetto › Postcards from Hell

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising – A Battle for the Ages

By Abraham J. Peck

On the fifteenth of May 1943, SS General Jürgen Stroop, whose forces had just destroyed the Warsaw Ghetto, reported that his troops had inflicted thousands of casualties on the Ghetto’s Jewish inhabitants, had left no major building standing, and had triumphed over a rag-tag force of Jewish resisters. “The Jewish Quarter in Warsaw,” he summarized with absolute finality, “is no more.”

On the surface, it would seem, such an action was merely another step in the planned destruction of Europe’s Jewish population, the Nazi “final solution” to an age-old problem of what to do with a “crafty” and “domineering” “other” whose first transgression had been the accusation that they had murdered the son of God.

But understood more deeply, the twenty-eight day uprising by a few hundred poorly-trained and poorly-armed remnants of what once was a ghetto of nearly 400,000 Jews packed into a tiny area of Poland’s capitol city, was far more. The Warsaw Ghetto revolt was, as one of its participants, Professor Israel Gutman, wrote, “literally a revolution in Jewish history.” A revolution? A revolution, when a mere handful of young Jewish men and women, members of Zionist, Communist or Bundist/socialist organizations, survived the furious assault by thousands of Nazi soldiers and their Baltic helpers, to emerge on the “Aryan” side of the city from sewers accustomed to carrying only slime and waste?

Think of it: think of the year 73 CE, just three years after the fateful destruction of Judaism’s Second Temple, when hundreds of Jewish combatants murdered each other and finally themselves rather than submit to an overwhelming Roman force. The site was called Masada.

Think of it: think of the years 132-136 CE, of the failed revolt led by the pseudo-Messiah, Simon bar Kokhba, when more than half a million Jews, including the great Rabbi Akiva, were slaughtered by Roman troops.

A revolution? Do we not acknowledge both of these ancient Jewish actions as revolutions in Jewish history, as major symbols of Jewish resistance and determination? Then we must also see the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in the same way, an event that took the Jewish people from enforced passivity to an active armed struggle for the first time in over eighteen centuries.

We should not look upon the month-long struggle of Warsaw Jews as a defeat. Victory was never an option, nor was the choice to either live or die. What makes the Uprising a victory was the fact that it allowed these heroic young men and women to choose their only option—how they would die—in battle rather than in the crematoria of Treblinka or in the grasp of starvation and disease.

How can we possibly see the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising as anything more than a terrible defeat in an age when winning is symbolized by the spoils of wealth and notoriety? We forget that our nation was founded on a principle of freedom from tyranny and that that principle was enforced in the stirring words of Patrick Henry as he spoke to the Virginia Convention on March 23, 1775, in an effort to convince that American colony to enter the Uprising against Great Britain:

Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

Millions of American men and women have stood in harm’s way through numerous conflicts protecting that same principle and putting their lives at risk so that America might continue to stand as the symbol of liberty and freedom.

Those young Warsaw Jews who vowed to die in battle rather than submit to the Nazi effort to destroy them through disease and starvation found their liberation in armed combat, their majesty in the futility of resistance.

Their heroic struggles have served as an inspiration to many who see their own choices as similar to those that faced the Ghetto fighters. That is because the evils of genocide, the brutal reality that marked every Jewish man, woman and child for destruction during the years of the Holocaust have not disappeared. Genocide does not discriminate on the basis of geography, skin color or religious belief. Now, as then, it waits for the opportunity for a group to be designated as “the other” in a society that is prepared to carry out the wishes of its leaders to the point of mass murder.

Young Americans, lucky as they are to be spared the hateful ideas of a genocidal society, cannot afford to look away in the face of such evil. They must understand it, face it, and help in the effort to overcome it. That effort begins in their own back yard, in their own school, in their own community. It ends when they become the generation of record, the generation that will guide America and ensure that our nation never looks away in the face of discernable evil and the wanton destruction of human life.

Audio version read by Abraham Peck

Abraham J. Peck is the director and Visiting Professor of Holocaust, Genocide and Human Rights Studies at the University of Maine at Augusta.

“Nor Will Our Deaths Be Meaningless”1: The Destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto

By David Kriebel

The destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto stands as a turning point in the history of the Holocaust, when persecution and abuse of Jews became state-run slaughter.

Following the 1939 German invasion and the defeat of Polish forces, the occupiers instituted a policy of concentrating Jews and Polish refugees in the Warsaw Ghetto, the Jewish Quarter of the Polish capital, comprising about 100 square blocks. Most Jews in the Ghetto tried to downplay their ethnicity, but the Nazi occupiers insisted on setting them apart, forcing them to wear an armband emblazoned with a Star of David. Finally, in October 1940, the Nazis ordered the evacuation of all Christian Poles from the Ghetto and at the same time, packed the area with Jews from other parts of Nazi-occupied Europe. The Ghetto was sealed off. About 400,000 people lived there at its height, in conditions of extreme poverty, ravaged by hunger and disease, and subject to Nazi terror. Once it was sealed, the Ghetto was systematically liquidated.

The Ghetto served as a staging area for the transport of Jews to death camps, particularly Treblinka, a process known as “resettlement.” Jews were deliberately starved, given food rations of only 200 calories per day. To survive, some resorted to stealing food or selling their bodies. Others became collaborators, working with the Nazi-sponsored Jewish Council or as Gestapo agents. But most tried to maintain as normal a life as they could, hoping for rescue. At first, the Ghetto’s inhabitants believed that those deported from the Ghetto were being sent to labor camps. Once it became clear that “resettlement” meant extermination, armed resistance broke out. The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising lasted from 18 January to 16 May 1943, with the most intense fighting in the last month. To finally quell the uprising, the Germans bombed the Ghetto block by block, reducing it to rubble. A concentration camp for 2,000 Jewish and Christian prisoners was built in its place.

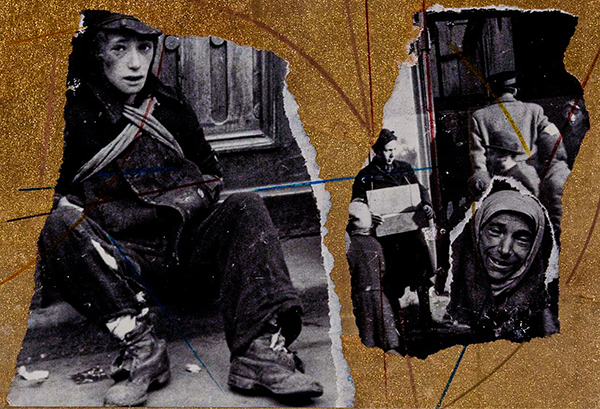

The Ghetto is well-documented in photographs taken by Germans, some of which are captured in Bob Barancik’s “Postcards from Hell.” Some of these images were taken by the authorities to demonstrate the supposedly subhuman nature of the Jews, encouraging anti-Semitism. Other photos were taken by German soldiers touring the area, sometimes with their girlfriends—a sort of genocide tourism. Despite this, Allied leaders did not believe or did not want to hear the testimony of Polish resistance officer Jan Karski, who furnished the first evidence of a Nazi extermination program.

The sealing of the Warsaw Ghetto separated Jews, not only from their fellow men and women, but from their humanity. It is by making such deadly distinctions that genocide becomes possible. Nor are the perpetrators left undamaged. The callousness of those who snapped souvenir photos of hopelessness, starvation, and death testifies to that. But there is also the example of those who resisted—Jews, like Mordechai Anielewicz, who took up arms in the Uprising; Christians who supplied food and materials, or sheltered Jewish children; or those everyday people who simply persevered in the face of death and indignity, carrying on so that we might never forget.

1 From Ringelblum, Emmanuel (2006). Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto: The journal of Emmanuel Ringelblum. Translated and edited by Jacob Sloan. New York: ibooks. 296. Back to essay

David W. Kriebel is an anthropologist and writer currently teaching part-time at Eastern University and pursuing graduate study in psychology at Bryn Mawr College. He holds a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania and an M.F.A. in creative writing from the University of Maryland. He has taught humanities and social science at several other colleges and universities, and worked as an analyst for the U.S. government.

Related Essays by Dr. Abraham Peck

Abba Kovner: Was the Pen Still Mightier than the Sword?

Like Sheep to the Slaughter? Jewish Resistance during the Holocaust

Art & Concept: Bob Barancik

Voice: Aleshea Harris

Media Production: Beth Sullivan

Audio Production: Mark Maynor

Photoshop Consultant: Scott Watkins

Postcards

Tech Notes

The 4x6 inch cards are heavy rag cotton paper with mixed-media photo collage on the front and short cryptic messages on the back in a haiku format. An actual stamp from the period of German occupation of Poland is included as a historical artifact. The cards reside inside of an archival mylar sleeve. The custom made box is also archival.